Grabpflege

Literally grave care, it's the German word for tending to the graves of one's loved ones. They made a word for it, because it is such an important part of the culture.

I'm currently visiting Berlin and yesterday headed over to one of my old haunts, the Dokumentationszentrum Berliner Mauer, to see if anything had changed since I finished my thesis on the Berlin Wall in 2005.

In order to get to a very interesting section of original Wall that was removed in 1989, you have to enter a neighboring cemetery and walk through the gravestones. Very few people know or do this, even though I was impressed at how many visitors the Center seemed to have that day.

My mom was recently joking about me liking cemeteries, because it's not unusual for me to seek them out while we're traveling -- less in search of famous people (no dancing on Jim Morrison's grave here) and more in search of gravestone art and the peace of a park of the dead. Moscow's Novodevichy and Prague's Vinograhdy are two of note. (I guess having two favorite cemeteries must make me a little weird.)

This cemetery in the Bernauer Street is totally mediocre except for its history. It came to fall on the "front line" between East and West Berlin, and therefore neighbored the Berlin Wall for the Wall's 28-year existence. In order to visit and tend graves in this highly secured border area, East Germans had to apply for a permit. Only closest relatives -- grandparent, parent, child, brother, sister -- were granted such exceptions for fear of attempts to cross to the West. Those relatives who suddenly found themselves on the western side of the Wall were now unable to visit the graves at all, an everyday concern that illustrates the absurdity of drawing a dividing line through a modern city.

The care Germans give the graves of their loved ones is extreme by American standards. My dad's secretary yearly places a planter of flowers on her father's grave -- probably on Memorial Day -- but asks my father to go and water them, since we live much closer to the cemetery than she does. My grandparents' plots are so far away that I've only visited their parched eternal resting places once. My parents have bought adjacent plots, meaning that I will only rarely visit their graves as well. For people like us, cemeteries have subscription services of flag planting and flower watering, in addition to the lawn mowing and other care they already provide.

This would be unimaginable here, where I passed graves that not only had spring bulbs planted by a loved one blooming, but also new bouquets of fresh flowers. Of course, this is not every family and every grave. But it is many and it is overwhelming. On graves of people who died the year I was born. That is 26 years of actively tending to a grave, a ritual I appreciate and yet will never participate in. I imagine grave care as a ritual of the old, of the recent widower or of the aged wife and children of the family patriarch. Since I don't really know, I thought it would make a great anthropological study -- what keeps habitual gravetenders coming back? What do they do while at the grave? Who is this ceremony for -- the loved ones or themselves? Add to this the history of this cemetery -- did this loved one die while you were in West Germany? Were you not permitted to visit this grave for decades? Is this a form of atonement for your absence, for a divided Germany?

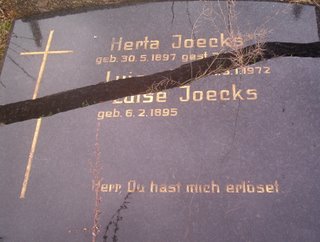

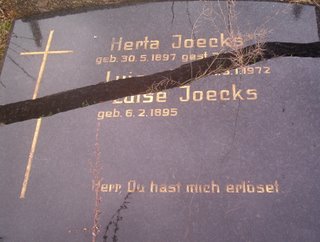

Behind the pieces of Wall I was headed for was a (excuse the pun) graveyard of old and broken headstones from untended, unloved graves. Here a couple images from the scrap heap of the eternal sleep.

In this image, you can see some of the heap in the foreground. In the near background, by that sand or dirt mound, are the backs of the original Wall elements.

Poor Charlotte.

What do you suppose happened to Luise? Buried in West Germany? Still alive?

I'm currently visiting Berlin and yesterday headed over to one of my old haunts, the Dokumentationszentrum Berliner Mauer, to see if anything had changed since I finished my thesis on the Berlin Wall in 2005.

In order to get to a very interesting section of original Wall that was removed in 1989, you have to enter a neighboring cemetery and walk through the gravestones. Very few people know or do this, even though I was impressed at how many visitors the Center seemed to have that day.

My mom was recently joking about me liking cemeteries, because it's not unusual for me to seek them out while we're traveling -- less in search of famous people (no dancing on Jim Morrison's grave here) and more in search of gravestone art and the peace of a park of the dead. Moscow's Novodevichy and Prague's Vinograhdy are two of note. (I guess having two favorite cemeteries must make me a little weird.)

This cemetery in the Bernauer Street is totally mediocre except for its history. It came to fall on the "front line" between East and West Berlin, and therefore neighbored the Berlin Wall for the Wall's 28-year existence. In order to visit and tend graves in this highly secured border area, East Germans had to apply for a permit. Only closest relatives -- grandparent, parent, child, brother, sister -- were granted such exceptions for fear of attempts to cross to the West. Those relatives who suddenly found themselves on the western side of the Wall were now unable to visit the graves at all, an everyday concern that illustrates the absurdity of drawing a dividing line through a modern city.

The care Germans give the graves of their loved ones is extreme by American standards. My dad's secretary yearly places a planter of flowers on her father's grave -- probably on Memorial Day -- but asks my father to go and water them, since we live much closer to the cemetery than she does. My grandparents' plots are so far away that I've only visited their parched eternal resting places once. My parents have bought adjacent plots, meaning that I will only rarely visit their graves as well. For people like us, cemeteries have subscription services of flag planting and flower watering, in addition to the lawn mowing and other care they already provide.

This would be unimaginable here, where I passed graves that not only had spring bulbs planted by a loved one blooming, but also new bouquets of fresh flowers. Of course, this is not every family and every grave. But it is many and it is overwhelming. On graves of people who died the year I was born. That is 26 years of actively tending to a grave, a ritual I appreciate and yet will never participate in. I imagine grave care as a ritual of the old, of the recent widower or of the aged wife and children of the family patriarch. Since I don't really know, I thought it would make a great anthropological study -- what keeps habitual gravetenders coming back? What do they do while at the grave? Who is this ceremony for -- the loved ones or themselves? Add to this the history of this cemetery -- did this loved one die while you were in West Germany? Were you not permitted to visit this grave for decades? Is this a form of atonement for your absence, for a divided Germany?

Behind the pieces of Wall I was headed for was a (excuse the pun) graveyard of old and broken headstones from untended, unloved graves. Here a couple images from the scrap heap of the eternal sleep.

In this image, you can see some of the heap in the foreground. In the near background, by that sand or dirt mound, are the backs of the original Wall elements.

Poor Charlotte.

What do you suppose happened to Luise? Buried in West Germany? Still alive?

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home